Article By Shreyansi Shrestha

In the ever-evolving world of art and culture, we often find ourselves caught in an ethical dilemma: should we embrace modernity, experiment, and adapt, giving a floor for the new unique rawness, or uphold tradition and carry forward its legacy? This question becomes even more pressing when considering the role of art in our personal and professional lives—should creativity remain pure and untouched by commercial influences, or is financial success a valid and even necessary part of an artist’s growth and independence? But who decides what is “right” or “wrong” in art? Is art meant to be an exclusive pursuit of beauty, or should it challenge, provoke, and raise awareness of important issues? Can it embody darkness, offering comfort to those who relate to it, rather than just appealing to conventional standards of aesthetics? And in an industry where competition is inevitable, how do we define it—does it become a divisive “you vs. me” struggle, or can it exist in a way that fuels creativity without overshadowing artistic integrity?

Let us try to untangle the story, if not the solutions, via Street’s Elemental Flavours.

With time comes evolution, and there will not be adequate space for today’s artists and art if street spaces and people do not provide them a chance to experiment with their styles. After all, we are here to log activity of the current generation as well, and not just place the past at the forefront. So, the room for “new” should never be compromised in the name of preserving legacy.

Beginning with the first elemental flavour – Street Art:

Street Art provides a voice for all kinds of emotions. Because it is alive in public spaces and often unpredictable, it gives a fresh way to think, question, or create opinions and perspectives in its passers-by. It serves as an inclusive medium for all – providers plus the seekers. In the midst of the artistic dilemmas previously discussed, a pressing question emerges—one that resonates deeply within the fabric of our society. In a country like Nepal, where political instability frequently disrupts the status quo, can we truly reduce protest to nothing more than mass demonstrations and physical confrontations? Or is there space for a more thoughtful, yet equally powerful, form of resistance—one that speaks not through shouting or violence, but through silent creative protests?

Graffiti is a prime example of this, with a history deeply rooted in rebellion, self-expression, and the desire to be heard in a world that often silences the marginalised. It began in the late 1960s in New York City, where young people, mostly from low-income and minority backgrounds, used public spaces as their canvas. These early graffiti artists—often called “writers”—started by tagging their names or initials on subway cars and public walls. The aim was not necessarily to create something beautiful but to gain visibility, claim space, and make a statement in a city that often ignored them. The first signs of graffiti were simple, but as the movement grew, artists began to experiment with colourful, intricate murals, elaborate letters, and even political messages. Graffiti became a way to challenge authority, express frustration with social inequality, and assert identity in an urban environment. These acts of expression were not always welcomed by authorities, leading to constant tension between street artists and city officials who saw graffiti as vandalism. Over time, graffiti evolved into a global art form, spreading across countries and becoming a symbol of resistance. What started as an underground, rebellious act transformed into an internationally recognised genre of art.

In Nepal, like in many places with a complex political landscape, graffiti has the potential to serve as a powerful tool for change, becoming a voice for the marginalised—a subtle yet potent form of protest that bypasses traditional channels and speaks directly to the public and the government. There are many talented graffiti artists in Nepal who are daringly chasing that unconventional path.

For instance, muralist Laxman Shrestha, the man behind “Khoj” art outside Kathmandu’s Bir Hospital and many other prime locations, shared that less media recognition is one of the main reasons behind artists finding it difficult to bring an all-round value to their work. He also mentioned that art is not just about the “pretty”, but distorted and intentionally disoriented things as well, as these things together represent both the good and bad sides of society. Street art, he said, is the truest form of social representation, reflecting society in its rawest form.

Graffiti artist Mister Do shared that in Nepal, graffiti is still not widely accepted as a valid art form, even when done ethically. He feels this is mainly due to a lack of awareness, as understanding of graffiti is mostly limited to the hip-hop and underground scenes. To him, street art should be a raw, independent voice for justice—free from intermediaries.

Another graffiti artist who goes by the name Stoc views the growing presence of street art in Nepal as a sign of cultural and youth evolution. He believes the rise in public murals reflects shifting social dynamics and sees graffiti as a personal expression of joy, voice, and presence. While acknowledging that every artist has their own style and perspective, he emphasises that the way forward—both artistically and commercially—is to stay true to what one genuinely loves.

While rebellious/dark street art speaks raw truth, serene and decorative wall art also pleases the public eye. Notably, KMC has supported themed murals—like sports art outside Dashrath Stadium—which is commendable. However, it is also concerning that in some places, independent street art has been erased. This raises a crucial question: Is “decorative” the only acceptable form of art? Art reflects human emotion, and people don’t feel “good” all the time. Sadness, anger, and vulnerability are just as real as joy. Why is art that captures sadness not deemed “beautiful”, when every emotion—whether joy, sorrow, or vulnerability—deserves to be valued and respected? Giving all emotions space in public art allows people to feel seen—and more empowered to express themselves fully.

Moreover, for a truly vibrant cityscape, street art extends beyond graffiti/murals to include the work of designers behind banners and ad campaigns. These creatives bring life to urban spaces, blending art with purpose. Britannia’s campaign is a striking example—merging nature and design to create visuals that were both eye-catching and meaningful. Such work shows how design in the streets can be more than promotion—it can be a form of public art that engages and inspires.

Another elemental flavour of the street is Street Music:

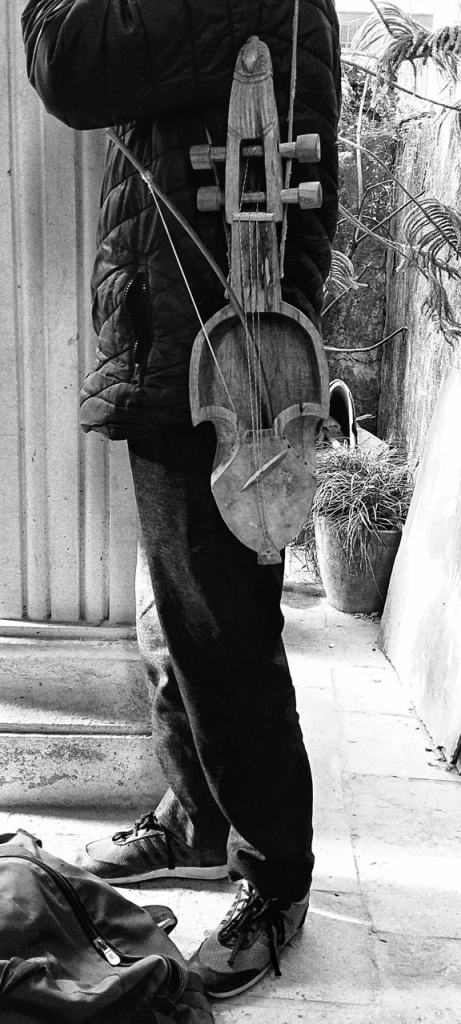

Street Music/Busking is the heartbeat of the streets—where music meets the open air, and creativity blooms in public spaces. It is the soul of the city, where every note played or song sung draws energy from the environment and gives it back to the people. Be it that country or reggae singer with a guitar, or a sarangi player, or any instrumentalist showcasing their craft.

Narayan Gandharva (Gaainey Dai) shared that his craft gives him a sense of purpose and has sustained his life. With his sarangi held tightly to his chest, he sings, pouring his soul into each note. Hailing from the Indo-Aryan ethnic group in Nepal’s central hilly region, Gaainey embodies the beauty of culture, art, and music within Nepal’s Dalit community. His music reflects not only his heritage but also the lives of those around him, giving each street a unique meaning. However, while busking can be a respected art form, some use loudspeakers and gimmicks for money (only), overshadowing true street musicians who have spent years perfecting their craft.

Safic, the voice that gave life to the iconic busking anthem “Walking Firiri” with Gorkhali Takma Band, considers busking to be the truest and most unfiltered form of artistic expression. He views busking as a way to share unheard stories, spark spontaneous connections to an audience the artist has never met before. “It’s where the artist and the public meet without barriers,” he said, “whether it’s singing, dancing, writing, sketching, or painting.” He further noted that it also holds the potential to deliver impactful social messages to the public.

Yet despite its creative potential, he said the busking scene in Nepal continues to struggle, weighed down by red tape and a lack of institutional support. Even in culturally vibrant areas like Thamel/Freak Street, Safic pointed out that performers are required to go through a complicated approval process involving multiple government bodies. Drawing comparisons to countries like Thailand, Singapore, Japan, and South Korea, he explained how young violinists, pianists, and singers in those places perform confidently on the streets—covering songs, building stage presence, and receiving public encouragement. He explained that the public’s encouragement stems from their desire to see the younger generation get deeply engaged in artistic pursuits as well.

As a potential solution, Safic suggested that authorities, including those managing heritage sites, metropolitan areas, and district administrations, could collaborate to offer greater support to street performers. He proposed the idea of introducing a licensing system that would not only legitimise busking but also allow artists to express themselves more freely in public spaces. Furthermore, he envisioned a thoughtful programme where licensed buskers could perform on a rotating basis across prominent tourist destinations such as the valley’s heritage spaces, Pokhara, Chitwan, Ilam, etc. With the backing of local government bodies, such an initiative could help cultivate both the personal growth of artists and a richer cultural experience for the public.

Robin Wagle of the Robin Wagle Trio, a band known for blending folk, jazz, fusion, and global influences, also shared a thoughtful perspective reflecting on his time in Australia, where busking helped him gain confidence and manage stage anxiety. While he admits it was challenging and at times creatively limiting, he encourages young musicians to focus on creating opportunities they desire themselves, whether digitally or physically, even if it is at present non-existent, by refining their craft and seeking out spaces that genuinely appreciate their artistry.

Sarad Shrestha, lead vocalist and guitarist of Shree 3 (stoner rock, desert rock, grunge) and guitarist in Tumbleweed Inc. (rap-based funk/metal), and formerly The Axe Band, believes busking can provide a valuable platform for all genres, including underground and hardcore music, apart from just jazz or country music. He notes that with the right spaces and a bit more planning and consideration, especially regarding volume and potential audience reception, busking can become a unique, thriving avenue for musicians to connect with fresh audiences and grow their craft organically, especially in the present digital age, which he feels is tough for emerging musicians.

Sudhir Acharya, the percussionist (Dhime artist) for the new-school folk band Night, which makes use of traditional Nepali instruments in its music in a unique manner, expressed his thoughts on the common misunderstanding of buskers being seen as beggars. He clarified that buskers are not beggars, but rather artists who bring their craft to the streets, offering an authentic and valuable performance. He also emphasised that the best way to learn music is by exploring all genres, artists, and their histories, understanding the struggles behind them. Busking, in essence, reflects this diversity, with artists sharing a wide range of musical expressions on the streets.

Yaju Acharya, the flautist of all-girls rock band Istri’s, shared of not being very exposed to the busking scene here because people do not usually busk in Nepal. She further shared of seeing musicians busking only when they need to raise funds for the needy sometimes.

The dilemma between embracing modernity or upholding tradition, and the balance between artistic purity and commercial success, plays out vividly in the realm of street art and music. These street elements offer a raw and genuine form of expression, where emotions—both dark and light—find a voice, and where art challenges norms and provokes thought. Street art and busking allow artists to stay connected to their communities while also opening possibilities to commercial success by staying true to their art forms. They reflect the complexity of human experience, embracing all emotions, and remind us that art, in its truest form, should be inclusive, honest, and open to all perspectives.