Trigger Warning: Mention of suicide

Adolescence is a time of fast, and sometimes confusing changes. It is widely recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a critical and vulnerable stage of human development. Young people are not only growing physically but are also learning to manage new emotions, social pressures and expectations. When these challenges are combined with difficult experiences such as poverty, violence, bullying, peer pressure or the constant influence of social media, many adolescents become more likely to struggle with anxiety, low mood, and other emotional or behavioral problems. Their situation can become even harder if they face discrimination, live in unstable homes, or grow up in communities affected by conflict or crisis. These difficulties can affect their studies, friendships and confidence, and if they do not get the support they need, the impact can follow them into adulthood.

Globally, one in seven young people aged 10–19 lives with a mental health condition, many of which remain untreated due to persistent stigma, limited services and a general lack of awareness. In the context of Nepal, as per the National Mental Health Survey 2020, 5.2 percent of individuals aged 13–17 are reportedly living with a diagnosable mental health disorder in Nepal. Neurotic and stress-related conditions are the most common, affecting 2.8 percent, followed by phobic anxiety at 1.3 percent and major depressive disorder at 0.6 percent. The distribution of these conditions is not uniform across the country. Koshi Province has the highest prevalence at 11.4 percent, and adolescents aged 16 years show the greatest vulnerability at 7.7 percent. The data also indicate a slightly higher rate among female adolescents (5.3 percent) compared to males.

Despite clear signs of emotional and psychological distress, with 3.9 percent of adolescents reporting current suicidal thoughts and 0.7 percent reporting a past attempt, many young people hesitate to seek support. The survey points to several influential attitudinal barriers. For example, 22.6 percent of adolescents feel uncomfortable discussing their emotions, 15.6 percent fear being perceived as weak and 12.3 percent worry about how their family might react if they sought professional care.

Recent studies shows that the rise in suicide cases among Nepali youth is closely linked to family disputes, relationship problems, difficulty coping with stress, experiences of failure, and exposure to violence or domestic abuse. Experts also warn that the growing influence of social media—such as suicide contagion, online bullying, exposure to distressing content, and the pressure to seek validation through likes and views—is worsening the crisis. These factors, combined with stigma around mental health and limited access to timely support, have made adolescents particularly vulnerable. Researchers also note that Nepal’s suicide rate peaked at 16.9 per 100,000 in 2017 and 2018, and spikes were recorded following major national crises such as the 2015 earthquake, indicating how economic and emotional shocks intensify vulnerability.

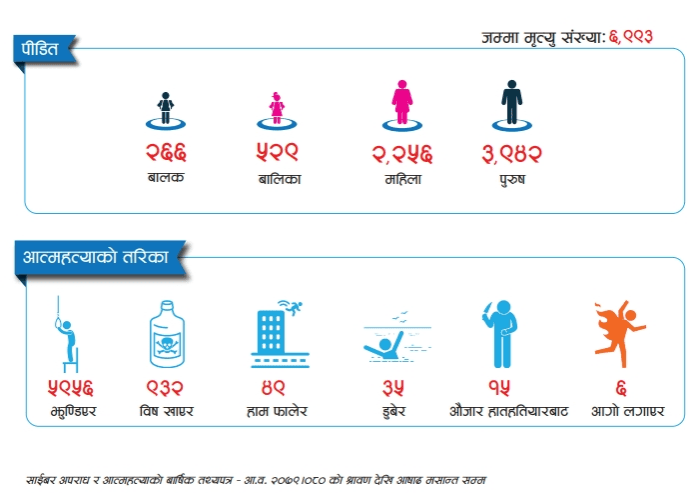

Nepal Police data show a sharp rise in suicide-related cases within a year. Annual factsheet report from Nepal Police on FY 2079/80 revealed that, Nepal registered 6,703 suicide-related cases nationwide in the latest reporting year. Koshi Province reported the highest number of cases that is 1,452, while Karnali Province recorded the lowest, 404. A total of 6,923 deaths were documented, affecting 3,454 men, 2,756 women, 529 girls and 266 boys.

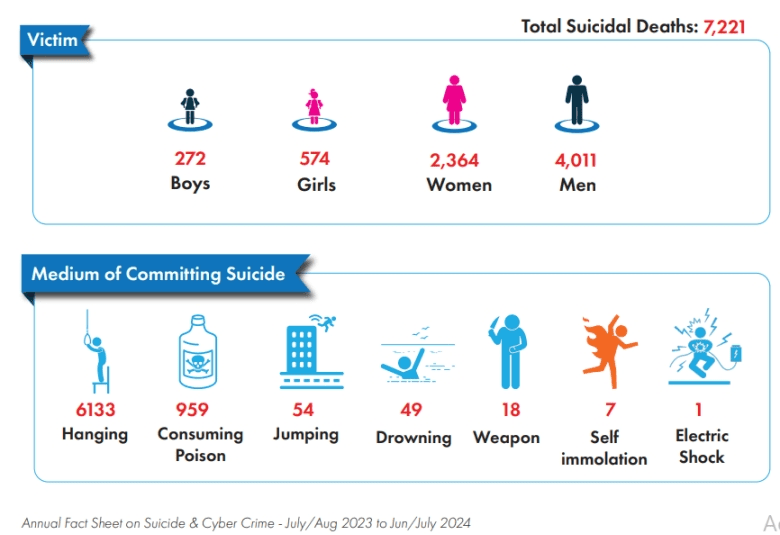

Annual factsheet report from Nepal Police on FY 2080/81 revealed that, Nepal registered 7,194 suicide-related cases in the last reporting year, with the highest numbers, 1554 cases reported in Koshi Province and the lowest, 327 cases in Karnali Province. A total of 7,221 deaths were documented, affecting 4,011 men, 2,364 women, 574 girls and 272 boys.

The year-on-year increase in both cases and deaths, coupled with consistently high numbers in Koshi and rising figures among minors, highlights deepening mental health challenges and widening gaps in support across provinces.

Nepal’s mental-health crisis is deepening at a pace far faster than the country’s systems can respond. Over the last decade alone, police records show that suicide deaths have risen sharply—from around 11 deaths per day in 2011/12 to 19 deaths per day in 2021/22, with more than 53,000 lives lost in ten years. According to the National Mental Health Survey, 6.5% of Nepalis report having thoughts about suicide, underscoring the urgent need for early support and stronger prevention mechanisms.

According to the spokesperson for Nepal Police, the major reasons for suicide among adolescents include rising levels of stress, anxiety, and depression—issues to which this age group is particularly vulnerable. Academic pressure, social expectations, poverty, genetics and limited coping skills make adolescents more prone to emotional struggles. Parenting conflicts and family disputes also contribute significantly, as do wrongful accusations that create deep mental trauma. Police reports further indicate that rejection or difficulties in romantic relationships have become increasingly common triggers of distress among teenagers.

In 2020, WHO in its Mental Health Atlas reported that Nepal’s mental-health system was severely under-resourced: the country spent 0.2% of its total health budget on mental health—just USD 0.10 per person—and had only 0.13 psychiatrists and 0.02 psychologists per 100,000 people. None of Nepal’s 18 outpatient mental-health facilities provided services for children or adolescents, and the country lacked a national suicide-prevention strategy, stand-alone mental-health law, and any rights-monitoring mechanism. The WHO-estimated suicide mortality rate was 9.77 per 100,000, with no significant decline in preceding years.

By 2024, WHO’s updated Atlas shows that these gaps remain largely unchanged. Low-income countries like Nepal continue to spend below USD 1 per capita on mental health, with the LIC median at USD 0.04, indicating Nepal’s spending has not improved. Workforce shortages also persist: LICs report only 1.1–2.4 mental-health workers per 100,000 people, and just 0.05 child and adolescent mental-health specialists, mirroring Nepal’s continued lack of youth-focused professionals. Outpatient community services remain scarce—fewer than 0.1 facilities per 100,000 population—and globally only 43% of mental-health laws meet human-rights standards, reflecting Nepal’s still-incomplete legal framework.

A recent scientific review of Nepal’s mental-health landscape shows that, although services have slowly expanded since the 1960s, the gaps remain overwhelming. Nearly 10% of Nepalis are estimated to experience a mental-health condition in their lifetime, yet 77% receive no treatment at all. Most professionals are concentrated in Kathmandu, leaving rural communities almost without formal care. Stigma, cultural beliefs, limited awareness, and the high cost of seeking help continue to hold many people back.

According to Dr. Arun Kunwar, Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist, the most common mental-health issues seen among young people today are anxiety and depression. He explains that the major causes include heredity and significant stress, which are often intensified by environmental, societal, and family-related factors. Nepalese society, he adds, still lacks a clear understanding of what mental health is, and both families and schools—where children spend most of their time—are often unaware that their children may be struggling.

Dr. Kunwar stresses that teachers and parents should be able to recognize early warning signs, such as changes in behavior, reduced communication, anxiety, difficulty sleeping, withdrawal from friends, or becoming unusually irritable or angry. He notes that children are unpredictable and highly dependent on their surroundings, yet families and schools frequently fail to cooperate effectively.

He shared an example of a 12- to 13-year-old girl who suddenly stopped going to school and began showing symptoms like vomiting, stomachache and headaches. When she was finally brought in for help, it was discovered that her fear began when a mathematics teacher punished one of her classmates for not completing homework, and she became terrified that she might be next. Dr. Kunwar explains that while some mental-health triggers come from within the child, many challenges persist because families, schools and communities do not work together to address them.

Regarding the treatment gap, he points out that children make up nearly one-third of Nepal’s population, and around 10% of them need mental-health support. However, Nepal currently has only few full-time operating child mental-health clinics. Around 95% of the students who need help are unable to avail the support they require. However, efforts are now being made to expand mental-health services to Karnali and Madhesh provinces, but the need continues to far exceed the available resources.

Sushmita Rajopadhya, Counselling Psychologist states that, “Among adolescents in Nepal, the most commonly observed concerns include persistent fears, panic attacks, loneliness, and emotional isolation. Many young people have also begun turning to anonymous social-media platforms to vent. While this gives them temporary validation, it can often reinforce their problems instead of helping them address them safely.”

As she is also a teacher beside a mental health coordinator, she adds, many students struggle with concentration and become trapped in cycles of overthinking, often showing signs of withdrawal, irritability and academic decline. These problems are intensified by classroom comparisons, academic pressure and unrealistic standards set by social media, which fuel body-image concerns and unhealthy habits like skipping meals. Online comparisons, jealousy and fear of missing out (FOMO) further increases stress, while parental pressure to choose unwanted subjects or careers leaves adolescents feeling less in control and emotionally overwhelmed.

To make a better effort, she suggests that teachers should be trained to identify early warning signs in students, such as withdrawal, difficulty focusing, reduced engagement or sudden drops in attendance, as well as emotional exhaustion linked to peer pressure or classroom comparisons. While many schools now have counselors and conduct awareness programs with mental-health professionals, sustained and consistent efforts—not one-time sessions—are essential to create real change. Schools would benefit from regular workshops for teachers on mental-health awareness, child psychology and emotional literacy, along with clearer policies, reduced stigma and systems that prioritize students’ emotional well-being alongside academic expectations.

Below are some helpful self-care strategies recommended by the World Health Organisation (WHO):

- Talking to someone you trust – sharing your feelings with a friend, family member or colleague can help reduce stress and provide emotional support.

- Taking care of your physical health – stay active for at least 30 minutes a day, eat balanced meals and get enough sleep to support overall well-being.

- Doing activities you enjoy – cooking, reading, walking, gardening or spending time with pets can help maintain a positive routine and improve your mood.

- Avoiding harmful substances – alcohol, tobacco and drugs may seem like coping tools but can worsen stress and mental health in the long run.

- Practicing grounding techniques – slow breathing and paying attention to what you can see, hear, smell or feel can help calm overwhelming thoughts and reduce anxiety.

Below are also a few important contact numbers for those seeking help:

- Nepal Suicide Prevention Helpline: 1166

- TPO Nepal (Transcultural Psychosocial Organisation): 1660 010 2005

- TU Teaching Hospital Suicide Prevention Line: 9840021600

- Patan Hospital Suicide Helpline: 9813476123